Olympic Games

The saga of timekeeping

Citius, Altius, Fortius; “Faster, Higher, Stronger,” goes the original Olympic motto. But those words are meaningless without the reliable measuring used to confirm all those (hopefully) record-setting achievements.

The Olympic audience is measured in billions… and even though the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics (held in July 2021) were marked by a ban on large gatherings, they captured the attention of over three billion people across the globe. For the Paris-held 2024 Summer Olympics, the numbers are expected to be just as colossal. And all eyes will be on the finish line, where records are expected to crumble — just as they have for all Olympic history over the past two thousand years.

The tiniest of gaps can sometimes make all the difference, and the emotional stakes are high. In 2008 in Beijing, American swimmer Michael Phelps won the gold medal during the 100 m butterfly with a lead of 0.01 seconds. That result, like all the others, depends entirely on the official timekeeper — who is under just as much pressure as every one of the competing athletes. While the games will take place under Omega’s watch until 2032, the competition is, and always has been, fierce among watchmakers, to be the Official Timekeeper of the Olympic Games.

SWISS WATCHMAKERS, ENDURANCE CHAMPIONS

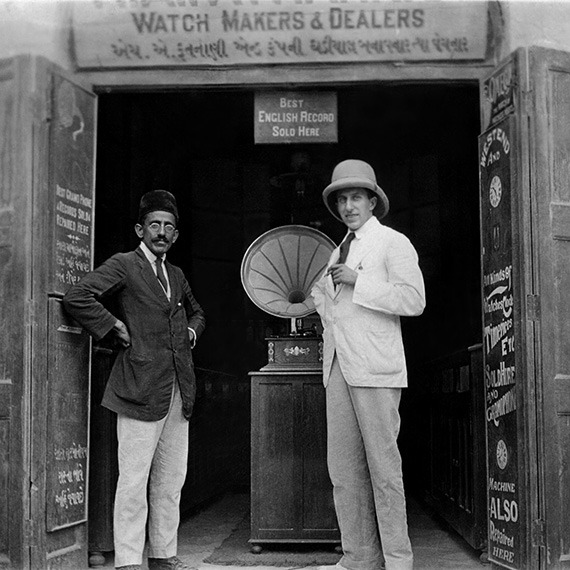

During the world’s first modern Olympic Games, which were held in Athens in 1896, Longines held the prestigious role of event timekeeper. Tag Heuer took over from 1920-1928, all while simultaneously beginning timekeeping responsibilities for competitive skiing and motorsports. Then in 1932, the title of “Official Timekeeper” made its debut under Omega.

Beginning in the 1950s, watch manufacturers began investing increasing amounts of money in sports sponsorship as a way of showcasing high precision. In 1964, Japanese watch company Seiko — using the precursor to quartz wristwatch technology — ousted Swiss watchmakers by becoming the Official Timekeeper for Tokyo’s Olympic Games. Four years later in Mexico, Omega returned, and then retired from the event due to rising financial costs.

After the 1972 Munich games, Longines also passed the baton. Then the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry intervened; Omega and Longines committed to fair play by Olympic standards and were adopted under its aegis. This led to the formation of the Société Suisse de ChronométrageSportif — now known as Swiss Timing, owned by the Swatch Group. Tag Heur joined for a while, notably for timekeeping the 1980 Olympic Games. Although Seiko sponsored the Barcelona Olympic Games in 1992, Swiss Timing has been fighting tooth and nail for Swiss watchmaking ever since, and the Japanese brand continued to be timekeeper for other competitions instead, like the World Championships in Athletics and Tennis.

OMEGA, FROM THE MOON TO THE OLYMPICS

Swiss Timing has been the Official Timekeeper of the Olympic Games multiple times, often shining a spotlight on Swatch Group watch brands. But Omega came back solo for the 2006 games in Turin and the Beijing games. The effect on its reputation (and sales) in Asia was so remarkable that Swiss Timing gave the company a full monopoly for using event-branded marketing. The brand’s storytelling, which up until then had been tied to the first moon landing, then shifted to also encompassing the Olympic Games. Paris 2024 marks the 31st time the brand has been associated with the event.

START, STOP, RESET

Let’s go back in time. In 1932, Omega brought 30 manually activated watches, which were certified for accuracy by the Observatoire de Neuchâtel, to California for the Olympic Games in Los Angeles. Then from 1940-1960, an electronic revolution took place in timekeeping: computers began to replace pocket watches and chronographs because they were more precise. Three generations later (in 2018), the introduction of positioning systems and motion systems once again revolutionised the game. In the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, the Real Time Tracking System (RTTS) saw electronic chips built into competitors’ race bibs, which transmitted live, real-time tracking. Even better, these timing devices also benefit elite athletes, offering vast opportunities for self-improvement.

In Paris, these technologies offer a chance to reach new record heights with the collection of 2,000 data updates per second, combined with high-definition cameras, which are crucial for that photo finish. Artificial Intelligence is also in the mix for the first time, allowing new levels of interpretation, which are translated by computer systems into graphics that suit various audiences. But what role does emotion play amongst all this data? A perfectly enhanced role, in fact: these technologies allow billions of people to see and appreciate these athletes’ exceptional performances exactly as they were meant to be seen and appreciated.