Going with the flow in Geneva

Lake, river, and beyond

Strategically built where Lake Geneva lets out into the Rhône River, Geneva quickly became a centre for trade. First, for goods, and later, for ideas that helped transform the city into the tolerant, global, cosmopolitan, and everlasting icon it is today.

Seen from above, the large body of water glimmers comfortably in a wide basin between the Alps and the Swiss Canton of Jura: but is it Lac Léman or Lake Geneva? “That’s appropriation!” Vaud and Savoy residents may cry, enraged. Whatever you call it, Lake Geneva (as it’s known to English speakers) and Genfersee (for German speakers) puts Geneva on the map, even if they don’t call it “Lac Léman,” like the French speakers do.

Lacus Lemanus

Lake Geneva may seem as big as an ocean (minus the salt, of course), but in reality, this landlocked lake is 581.3 km2 and 309.7 m deep — deeper than the Bassin de la Manche in France. The largest lake in Western Europe, Lake Geneva even has its own tides, albeit small, of around 4 mm. In the Canton of Geneva, most of the attention is fixated on the narrow section known as Petit-Lac, as opposed to the Grand-Lac, which is wide, deep, and used to be referred to as “Lake Lausanne” (in case things weren’t confusing enough already).

François Rabelais wrote that a giant named Gargantua made the lake to satisfy his thirst, but geologists think otherwise. They say the lake is a memory… the memory of the phenomenal Rhône Glacier, which, during the last ice age 15,000 years ago, covered the current location of the city in 700 m of seracs! But even if the lake’s appearance has since changed, this large basin is still mostly river water, which enters the lake at the edge of the Canton of Valais and exits in Geneva on the other side, before continuing its long journey to the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of France.

A sea of possibilities

Where Lake Geneva ends is where the slopes of the city of Geneva begin. A kind of bottleneck, delineated by the Right Bank (home of luxury hotels) and the docks of the Bains des Pâquis, and the Left Bank (home of the Jet d’Eau) and the Eaux-Vives port and outdoor baths. Here, the slender Genevan water taxis known as mouettes, the historic CGN steamboats, leisure sailboats, and catamarans alike all take to the water. And one can’t forget the Pierres du Niton (Neptune’s Stones), two large glacial erratics made of granite from Mont Blanc, which are remnants from the last ice age, left by the Rhône Glacier.

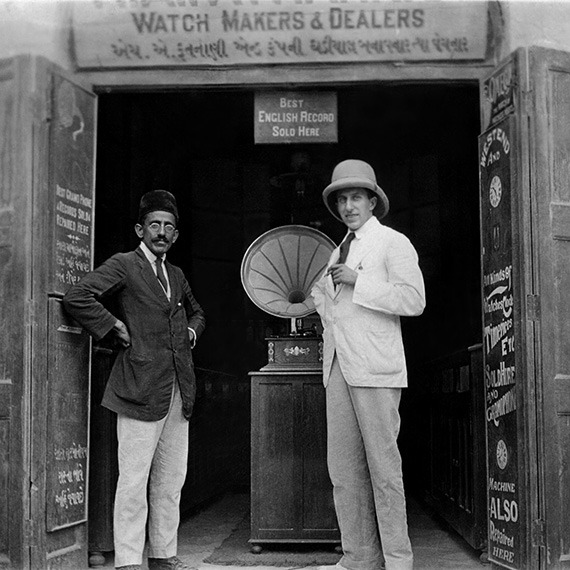

Baths to the north and beaches to the south… either way, we swim! We also stroll along the wide docks, meandering from patio to patio, accompanied by gulls, swans, and ducks. In the warmer months, the pop-up venues abound, often friendly and musical in nature. With a drink in hand, the Jardin Anglais and its iconic flowering clock beckon — a symbol of the city’s watchmaking traditions. Abundant sequoias, magnolias, and tulip trees surround the garden’s fountain, inspired by Neptune and built in 1863. The historic part of the city can be seen on a distant hill. It was on the top of that hill that medieval Geneva began, built up around the city’s cathedral. Seen from the summit of the 157 steps that lead to the cathedral’s bell, the city of 1 million Genevans unfolds below.

The outlet

Geneva in Gallic means “orifice.” In Ligurian, it means “the place of water.” Lots of water has run under the Mont Blanc Bridge since it was built in 1862. It is Geneva’s outlet, a border of sorts, with the lake on one side, the Rhône on the other, and Rousseau Island near the middle. The island resembles a carinated piece of confetti and has a collection of plane trees that cast shade over a statue of the philosopher (Jean-Jacques), who was born in Geneva. A walkway connects it to the pedestrian-only Pont des Bergues bridge. In autumn, thousands of starlings loudly gather here as they migrate south.

Downstream, there’s an old sand bank that’s simply known as L’Île (the island). A bridge here was destroyed by Julius Caesar in 58 BC to prevent the Helvetii advancement. Since then, other advancements have been made in this industrial area of the city. It’s home to Geneva’s former hydro power plant (which built the city’s first Jet d’Eau) and the Seujet Dam, complete with floodgates and a beaver-friendly fish ladder.

The Sentier du Rhône hiking trail unfolds on the quiet Left Bank. Here, nature dominates over concrete. Benches, lush lawns, and barbeques encourage taking a break while dipping your feet in the clear turquoise water, full of promise. On hot summer days, a few brave souls take the plunge and drift downstream on buoys, passing the Pointe de La Jonction, where the Rhône and the Arve (with its cold, cloudy waters) meet, and on to the Verbois Dam, 12 km further downstream. Keep an eye out for canvasback ducks, foxes, badgers, and kingfishers along the way!